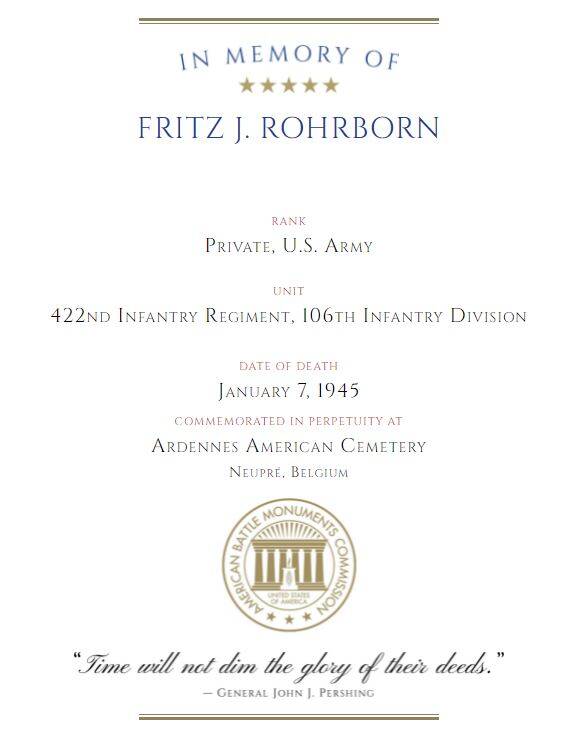

Private Fritz J. Rohrborn

US Army - WW II

Service number: 39011975

422nd Infantry Regiment - 106th Infantry Division

Born: 27 January 1918

Date of death: 7 January 1945 - Age 26 - Stalag IV-B - Mühlberg, Germany

Status: POW / DNB

Buried: Plot B Row 7 Grave 17 - Ardennes American Cemetery

Awards: Bronze Star

BIOGRAPHY

1941

Fritz entered service on Oct 8th, 1941 in San Francisco, California, at the age of 23.

He was 62 inch, weight 126 lbs.

1944

The 106th Infantry Division went overseas Nov 10th, 1944 and arrived in England Nov 17th.

After two weeks of routine camp life they shipped to France, arrived Dec 6th, and from there crossed into Belgium on Dec 10th where the 106th relieved the 2nd Inf. Div., Dec 11th in St Vith. After two days of organizing, the 106th began a twelve-mile eastern march into a hilly portion of Germany known as the Eifel, part of the Ardennes Forest lying across the continuous borders of France, Belgium, and Luxembourg, and took up positions in Schnee Eifel, 12 miles east of St Vith, Belgium, the most exposed salient of the entire American front.

And just a few days after taking position, suddenly the 106th Infantry Division was engulfed in one of the largest battles of the war: the Battle of the Bulge. The attack began on Dec 16th at 5.30 AM with a tremendous artillery barrage, the sky flashed as flights of German “Screaming Meemies” with ear-splitting shrieks tore over the treetops on their way to destroy St. Vith. Wire communications failed and radio frequencies were jammed.

The ferocious impact of shells from fourteen- inch German railroad guns shook the earth as a coordinated artillery barrage fell on the line companies, unit command posts, road intersections, and artillery batteries, all the division’s strong points..

Two hundred thousand German troops—crack, battle-tested infantry—protected by six hundred carefully hoarded Panther and Tiger tanks, were attempting to punch a hole in the American line of eighty thousand troops. The weakest point in the Americans’ defence was the salient of the 423rd and 422nd regiments, because the 106th had replaced the 2nd without making a single strategic change. At 9:00 AM, a second German artillery barrage, which was reported to be “unbelievable in its magnitude,” began pounding the two regiments, trying to erase them from the forest floor.

The 422nd, along with the 423rd, was engulfed by the overwhelming weight of the German breakthrough spearhead in an attack that continued through nightfall. By mid morning the next day, the 422nd 423rd and 424th regiments were forced to withdraw. At 3:35 PM on Dec 18th the radio announced that all units of the two regiments were in need of ammunition, food and water. Because of the fog, parachuting supplies was out of the question. Cornered at last they gave up on top of a hill, weapons destroyed, marched out to the enemy. By 4.00 PM Dec 19th, they had surrendered to German forces and over the following days they were marched to Stalag IV-B, one of Germany’s largest prisoner-of-war camps.

Tens of thousands of American prisoners marched east, the temperature was about 0 degrees F, no food or water. For those without overcoats and blankets it remained cold, frozen feet was the complaint of everyone. The march continued until Thursday morning, Dec 21st, when the column arrived at a railroad siding of freight cars at Gerolstein, Germany. The guards threw open the doors of boxcars and ordered them to get in. The Germans packed in about 60 to 80 captives before locking the doors. There was only room enough to stand shoulder to shoulder. It was so tight that, if you picked your feet up from the ground, the pressure from the other guys’ bodies would hold you up. Except for cracks between the slats, the only air and daylight came from louvered openings in each of the four corners. It took almost two days to load several thousand men onto dozens of cars.

On the morning of the 23rd, the POW’s could see the Rhine River through the boxcar slats at Koblenz. In late afternoon, they felt the train slow as it rumbled into a railway yard marked Limburg. Sounds of the locomotive being disconnected made them wonder if they’d reached a camp. Then the engine chugged away, leaving them behind. A few hours passed and all of a sudden the worst happened, Allied planes overhead, the RAF shooting at the train believing the boxcars were transporting goods for the Germans. The bullets came right through and many died or were left by the side of the road . Hundreds of men, freed by the guards, leaped off and tried to run away. Those who headed straight out from the train entered a curtain of explosions and disappeared. Others took cover, or wobbled in the direction of a barbed- wire fence where there was a concrete shelter. Only one boxcar received a direct hit, killing sixty- three men inside. Rails were repaired, another locomotive was found and sometime the day after Christmas, Dec 26th, the train started up again. They travelled to a second destination, the POW camp at Bad Orb, but were refused because the camp was over capacity. The prisoners spent another day swaying in the boxcars until they arrived at Stalag IV- B in Mühlberg, Dec 27th, where the guards ordered them off . Instead of leading them through the main gate they herded everyone to a grove of pine trees and instructed them to lie down in the snow. During the night, some men froze to death.

On December 28th, at the main gate, an Australian watched a “large part of an American infantry division, the 106th, stumble into captivity.” Never before have you seen men so near the end of their tether. Plagued with dysentery, twisted with frostbite, starving, dirty, unshaven, staggering on their feet from exhaustion, a long line of men stumbles endlessly into the camp. Captured before they knew what hit them, marched hundreds of miles into Germany, stepping over the bodies of comrades who slumped to die in the snow, jolted for days in cattle-trucks and boxcars that were strafed and bombed by the Allied air-fighters, the Americans were only a shadow of themselves. As the men came in through the main gate, tossing their helmets in a pile, they received cast- off , frozen clothing with a distinctive red triangle to signify POW.

They were deloused and registered. Fritz was given POW N° 313601.IVB.

The POW’s were given a postcard as required by the Geneva Convention, to assure the family that they had come “through the whole God-awful slaughter without a scratch. . . . We prisoners will be the first sent home when peace is won, and then for a 90-day leave. This life is not bad at all. Contact the Red Cross for advice on parcels and dispatch them immediately.”

Stalag IV-B was not marked as a prisoner of war camp, so the allied forces were under the impression that it was a military base for the Germans. The German Air Force helped to promote this idea by flying their aircraft over the camp at low altitude to make it look as if they were coming in for a landing at the camp. The allied air forces would shoot at the slow flying German planes and often hit the prisoners of war and their barracks. After a few of these terrible mistakes, some of the prisoners took rocks and anything else they could use to spell out POW on the roofs of the buildings and on the ground to alert planes that flew overhead what kind of camp it was. Unfortunately many of the pilots thought that it was just an attempt by German soldiers to trick the pilots into not shooting at them and so many of the pilots continued to fire on the camp.

1945

With the Stalag so overcrowded, a work detail was formed for the city of Dresden, eventually 150 POW’s from the 106th were selected for Arbeitskommando 557, departing Stalag IV-B for Dresden on Jan 12th 1945. On April 25th, 1945 Russian troops liberated the prisoners of Stalag IV-B.

However Fritz died on Jan 7th, 1945 of disease and malnutrition and was buried in the nearby Neuburxdorf Cemetery, grave 580 in the Prisoner Of War section.

1947

In 1947, Aug 7th – 8th the AGRC started disinterment of 28 graves. Of the total exhumations from the cemetery, 16 were identified by dog-tags, names agreeing with the cemetery records, 5 graves (amongst them grave 580 – Rohrborn Fritz) had no bodies in them, although the boxes were still there. After thorough examination each of the coffins showed evidence of having contained bodies. The other graves were listed as unknown Americans.

The British 56th Graves Concentration Unit was contacted because they had disinterred British bodies at the same section, but their records showed they had nothing to do with the American graves in question. After the British the French Bureau of Displaced Persons was visited but so far they had no teams in Neuburxdorf. Further investigation was to be made to find out what became of the remains in question, in the mean time Rohrborn Fritz was listed in AGRC as “Unresolved Casualty”.

1949

From 1949 that part of Germany turned into “East Germany” and was a “Soviet zone”, it was difficult to not possible to get admission, the Soviets refused collaboration.

1950

Nov 2nd 1950 a letter was send from the Dept of the Army, Washington to the Commanding Officer, 7887 Graves Registration Detachment, New York.

Attached were copies of POW status reviews, amongst them a Red Cross Casualty Report for Pvt Fritz J. Rohrborn.

1951

On Jan 31st 1951 in the Headquarters of “7887 Graves Registration Detachment Operations Division Liège, US Army”, it was decided to review and determine the non-recoverability of the remains of the deceased in question, lost in the geographical area described as Stalag IV-B, Mühlberg, Germany.

1953

May 20th : note from Commander-in-chief, US Army, Europe to Commanding Officer, USAREUR QM Mortuary Service Detachment: it is advised as to the feasibility of placing this case on current search agenda for the purpose of re-investigating Neuburxdorf.

1955

Investigation Report, Headquarters USAREUR QM Mortuary Service Detachment, 7770th Army Unit, US Army.

On Dec 17th 1955, accompanied by the Sovjet Major Serganov and Sr Lt Anthol, a new attempt was made to recover the remains of the mentioned deceased. According to Mr Neumann, present mayor and Mr Kraus, the former mayor, two plots were used for the interment of POW’s. Front right for the French, Italian, Yugoslav and Polish. Rear left plot for Americans, British, Belgian, Dutch, Polish and Soviet deceased. The mayors accompanied us on our visit to the cemetery. The front right plot was, with exception of 18 graves, completely exhumed, the rear left plot was completely abandoned and overgrown with weeds.

A survey of the complete area indicated that 6 rows of approximately 22 graves per row had, at one time existed. In that it could not be determined what rows contained the grave sites of the missing American deceased it was decided that all 6 rows be excavated. Excavation began on Dec 19th, continued on Dec 20th and on Dec 21st the final row was exhumed. Remains interred in space 20 were accepted as decedent Pvt Fritz Rohrborn 39011975 on basis of favourable dental comparison.

It was learned during the cause of this investigation, that in the winter of 1945-46, members of the Soviet Army were observed removing all crosses erected over graves in the American-British plot, some numbered grave markers were broken off and lying in the vicinity of the graves. During the course of the numerous disinterment by various Allied units these stakes were at times covered by earth. This is probably a possible explanation as to why grave markers were found over empty graves.

1956

The remains of Pvt Rohrborn were identified on April 18th 1956 at 10.00h.

The date of burial in the Ardennes American Cemetery is July 12th 1956 and the flag was sent to his sister Ann on July 13th 1956.

On Saturday 30th March 2019 I had the honor to meet Joanne and Ralph Thomas, Joanne is the niece of Fritz Rohrborn and this was the first time she visited his grave. Mike Yasenchak, the superintendent, put some Normandy sand in the letters so they stood out on the headstone.